Scrap booking is many things—a hobby, a time machine, a glorified glue-stick gala. At its heart, it’s a way to preserve the mess and magic of personal and family history, typically stuffed into the likes of a book, a box, or, for the overachievers among us, a card that unfolds like a paper magician’s trick. It often involves photos, scribbled notes, ticket stubs, questionable napkin sketches, pressed daisies, and enough glitter to alarm most vacuum cleaners. Journaling, doodling, and lovingly curated chaos are part of the package. But this isn’t a newfangled craft. Oh no. If you think this all began with Pinterest, let’s hop in our metaphorical DeLorean and head back to the 15th century.

Spanning five generations of women—teachers, immigrants, dreamers, farmwives, and one chronic note-maker—Margaret L. Young unpacks what’s been handed down through mitochondrial DNA, family recipes, wartime whispers, and broken brooches. These aren’t queens or celebrities; they’re the women who kept the world turning while no one was looking—and who left breadcrumbs in the form of quilts, cookbooks, and scribbled notes in margins.

Scrap booking is many things—a hobby, a time machine, a glorified glue-stick gala. At its heart, it’s a way to preserve the mess and magic of personal and family history, typically stuffed into the likes of a book, a box, or, for the overachievers among us, a card that unfolds like a paper magician’s trick. It often involves photos, scribbled notes, ticket stubs, questionable napkin sketches, pressed daisies, and enough glitter to alarm most vacuum cleaners. Journaling, doodling, and lovingly curated chaos are part of the package. But this isn’t a new fangled craft. Oh no. If you think this all began with Pinterest, let’s hop in our metaphorical DeLorean and head back to the 15th century.

In 15th-century England, clever folks kept common place books—essentially intellectual junk drawers where they jotted

down recipes, quotes, letters, poems, and other things they didn’t want to forget (or misplace under the bed). Each one was a

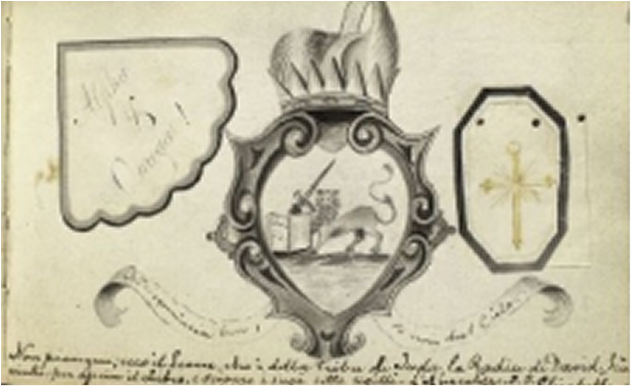

reflection of its owner’s obsessions and oddities. By the 16th century, friendship albums blossomed onto the scene—think: proto-yearbooks where your friends would inscribe a witty line, a doodle, or perhaps a cheeky Latin phrase, all upon request.

Often born out of European grand tours, these albums became cultural suitcases packed with coats of arms, mini paintings, and souvenirs from local artisans. Around 1570, colored plates depicting Venetian masks or Carnival scenes became the vintage version of album stickers—pasted in

Often born out of European grand tours, these albums became cultural suitcases packed with coats of arms, mini paintings, and souvenirs from local artisans. Around 1570, colored plates depicting Venetian masks or Carnival scenes became the vintage version of album stickers—pasted in not for their narrative power, but because

they were simply too fabulous to ignore.

Often born out of European grand tours, these albums became cultural suitcases packed with coats of arms, mini paintings, and souvenirs from local artisans. Around 1570, colored plates depicting Enter James Granger, 1775. He printed a history book with bonus blank pages—like Easter eggs for bibliophiles. Readers were encouraged to “extra-illustrate” the book with their own engravings, clippings, and commentary. The practice—later dubbed grangerizing—was essentially Victorian remix culture: cutting up, pasting in, and giving old books a makeover that even Marie Kondo would applaud. Venetian masks or Carnival scenes became the vintage version of album stickers—pasted in not for their narrative power, but because

they were simply too fabulous to ignore.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, friendship albums and school scrapbooks gave young women a voice beyond embroidery and polite piano recitals. They chronicled tea parties, heartbreaks, test scores, and dreams. It was legacy-building disguised as craft time. Take a peek at a Smith College scrapbook from 1906 and you’ll find a charming circus of doodles, dried flowers, calling cards, concert tickets, and maybe even a rogue spoon or two. These women didn’t just journal—they curated their lives.

When photography sashayed onto the scene in the 1820s, thanks to Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, it added a new layer of

memory-making to scrapbooks. Though photo albums didn’t take off until the 1860s, once the carte de visite became all the rage (think: selfie meets calling card), people couldn’t paste fast enough.

Scrapbooks soon became a mashup of images, captions, clippings, and keepsakes. A playbill wasn’t just a program—it was proof that you saw Bernhardt at the theatre. A dried rose? The whisper of a secret admirer. A guest list? Social clout in cursive.

And yes, even Mark Twain got in on the action. Ever the literary packrat, he toted scrapbooks on his travels, pasting in anything that caught his eye (or heart), which basically makes him the forefather of the souvenir hoarder.

Between 1795 and 1834, Anne Wagner—a woman in Percy Bysshe Shelley’s circle— kept a scrapbook that reads like a poetic

time capsule. Handwritten verses, locks of hair, ribbon scraps, painted cameos, and heartfelt notes from friends. Her album wasn’t just a book—it was a bouquet of relationships, carefully pressed and preserved.

In sum: scrapbooking is the act of turning life’s ordinary bits into a tapestry of meaning. It’s messy. It’s marvelous. It’s part historical archive, part heart-on-paper. And whether you’re wielding glitter glue or archival tape, it’s still one of the most human things we do—trying to catch time by the tail and paste it down for safekeeping.

1 Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Commonplace book. Wikipedia. Retrieved July 7, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/

wiki/Commonplace_book

2 Wikipedia contributors. (n.d.). Scrapbooking. Wikipedia. Retrieved July 7, 2025, from https:// en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scrapbooking 3 Gaskell, P. (1972). A New Introduction to Bibliography. Oxford University Press. 4 McGill, M. J. (2008). American commonplace: Ephemera and the scrapbook in nineteenthcentury America. University of Minnesota Press.

5 Blodgett, E. D. (2002). The scrapbook in American culture. Princeton University Press. 6 Rosenblum, N. (2007). A world history

of photography (4th ed.). Abbeville Press. 7 Darrah, W. C. (1981). Cartes de visite in nineteenth-century photography.

Getty Publications Twain, M. (1877). Mark Twain’s Scrapbook. American Publishing Company. 8 New York Public Library Digital

Collections. (n.d.). Anne Wagner scrapbook, “Memorial of Friendship,” 1795–1834. Retrieved July 7, 2025, from https:/digitalcollections.nypl.org/ items/510d47db-b630-a3d9-e040- e00a18064a99

ew York Public Library Digital 1 Collections. (n.d.). Anne Wagner scrapbook, “Memorial of Friendship,” 1795–1834. Retrieved July 7, 2025, from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/ items/510d47db-b630-a3d9-e040- e00a18064a99

12834 Cheverly Drive

704-575-0917

mlyordinarywomen@gmail.com

©Copyright 2025 MARGARET YOUNG. All Rights Reserved.